Mallikarjun Kharge’s election as Congress president also opens the way for more equitable alliances with the other opposition parties.

When Rahul Gandhi began his Bharat Jodo Yatra many, including this writer, wondered why he had decided to walk from the southernmost state of India to its northernmost and not from its westernmost to easternmost. This was because, with the exception of Karnataka, till Madhya Pradesh, none of the states that he planned to walk through had a Congress party left that was worth the name.

By contrast, had he decided to walk from west to east, beginning with Gujarat he would have traversed seven major states in which the Bharatiya Janata Party is in serious contention with a rival of greater or near-equal strength. In five of these, the Congress party is in power or has sizeable cadre strength, and four of those states are facing Vidhan Sabha elections between now and the end of 2023. Gujarat is the first among them. In each of these states, the Congress has a strong cadre base that can, with only a little extra push, upend a BJP that has not delivered on a single major economic promise it has made in the past nine years. So why, one wondered had Rahul chosen to go south to north, instead of west to east?

Today, two months later, his reasons no longer matter because two recent events have the potential to change the political calculus of victory and defeat in the coming 18 months.

The first is the Congress’ successful completion of Mallikarjun Kharge’s election as its president.

The second is the warmth with which Rahul Gandhi’s Bharat Jodo Yatra has been received in the south of the country.

Kharge’s election is a landmark because he is only the second non-Nehru-Gandhi president of the Congress since Indira Gandhi split the original party in 1969. His elevation has brought three new elements into the political calculus of the country’s future that were not there before. The first is that it has laid to rest the suspicion that the Gandhis were determined to keep the reigns of power in their hands at any cost, and resurrected the belief that Sonia Gandhi had only been doing so because she believed that keeping a member of Jawaharlal Nehru’s family at its head was the only way to keep the party from breaking up as it had almost done before she took over the Congress Presidency in 1999.

Rahul reinforced this when he came to Delhi to witness Kharge’s takeover as Congress president, by refusing to meet any of the Congress chief ministers who had sought a meeting with him and refusing to take part in the selection of candidates for the Gujarat assembly election. That, he made clear, was now Kharge’s business.

His and his mother’s unflinching resolve not to give short shrift to this still strong belief within the party cannot have failed to strike a deep chord within all Indians, but within Hindus in particular, because it resonates with two of the most powerful leitmotifs of the Arya Dharma. These are tyaaga – sacrifice – and sanyaas – renunciation. Rahul Gandhi and his mother have shown themselves to be capable of both in the wider interest of their country and their civilisation. The full impact of their renunciation will take time to sink into the people, but it has already begun to weaken the foundations of the BJP’s main appeal to the people: that the Gandhis are foreign by blood, are not Hindus, and do not even belong to the Hindu sanskriti (civilisational culture).

The second new element is that the unexpectedly warm reception that Rahul Gandhi has received in the three states that he has visited in his Bharat Jodo Yatra so far. To understand the warmth of his reception it is necessary to look beyond the short, grudging news clips that television channels , and mainline newspapers are giving it, and revisit a TV interview he gave to GSTV, and India Today before the Gujarat elections in 2017. That interview reveals not only the immense effort he had made to understand the problems being faced by Gujarat’s unemployed youth, its farmers and its womenfolk, but also his innate warmth and considerateness towards others, including his interviewer on the programme.

None of this was coming through, indeed could come through, when he was giving stilted, prepared, speeches to large gatherings from the safe distance of a dais that was at least 10 metres from his nearest listeners. But during the Yatra people have been seeing, and interacting, with him at close quarters. So they are feeling the impact of his sincerity and innate decency, for the first time. A different image of him and his party is therefore beginning to unfold. This change of perception is apparent even in the brief commentaries of the hard-bitten reporters who have been covering the yatra at different places along the route.

There is a third new element too – Kharge’s election has cleared the way to the formation of an alliance among opposition parties that the Gandhi loyalists in the party had spared no pains to prevent without a prior assurance that it would be led not only by the Congress, but by the Gandhis in particular. Sonia and Rahul Gandhi’s withdrawal from leadership signals a formal withdrawal from the pyramidal, leader-centred party structure that had emerged within the Congress after Indira Gandhi split it in 1969. It has therefore re-opened the way for a return, in different form, to the consensus based decision-making among powerful regional leaders, that had been the mode of decision-making in the party throughout its seven decade fight for India’s independence and till the death of Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru.

This has opened the way for the creation of a different, looser coalition that will be based not around personalities and charisma, but around shared political and economic concerns, and the need to stem the creeping destruction of India’s ethno-religious plurality that has been Modi’s goal virtually from the day he came to power.

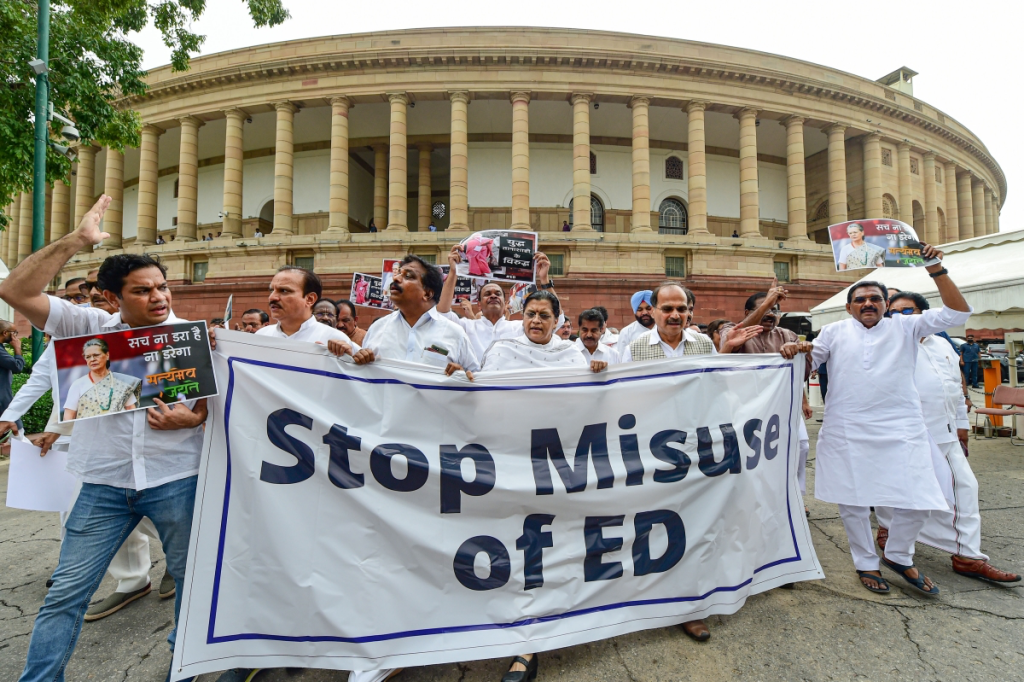

Just how quickly Prime Minister Modi has understood the threat that this change of perceptions poses is reflected by his most recent diatribe against ‘Lutyens Delhi’ at the annual state home ministers’ meeting in Faridabad. In it he turned his guns against ‘not only those Naxals who hold a gun but also those who wield a pen and mislead the youth by exploiting their emotions’. To his party’s determination to tame the Muslim minority through police action; to tame the political opposition through misuse of the Prevention of Money Laundering Act; and to destroy civil rights activism through fabricated charges of sedition and subversion against its leaders, Modi has now added the threat of jailing intellectuals and journalists who criticise his government in writing, under one cooked up pretext or another.

But in politics every action gives birth to a reaction. Modi’s increasingly brazen assault on all four of the pillars of Indian democracy, has brought it home to all opposition parties that they will have to swim together if their members do not wish to perish singly. This awareness, and the desire to form a common platform, had been growing for some time but had been stalled by the Congress’ insistence that it had to be the leader because it is the only party with a strong presence on the ground in all the states of the country where the BJP is now the dominant party.

Kharge’s election has removed this obstacle. His long association with Sharad Pawar virtually ensures that the Congress, Pawar’s National Congress Party and the Shiv Sena will fight the BJP together in Maharashtra in the next Vidhan Sabha election. Should this happen it is difficult to see how the BJP can avoid a rout in the next Vidhan Sabha elections. Unfortunately those will come after the next Lok Sabha elections where another BJP win could easily have sealed the fate of democracy in India.

But there is another immediate opportunity to strike a blow to the BJP’s supremacy and it is only weeks away, in the Vidhan Sabha elections in Gujarat. Somewhat inexplicably, after his September 3 visit, Rahul Gandhi has so far refused to visit Gujarat at all. This inexplicable abandonment of a powerful Congress party organisation gave the state BJP chief the opportunity to tell the people that Rahul Gandhi has “no place in his heart” for Gujarat. This may be the reason why opinion polls are predicting an easy win for the BJP. But that will only happen if the discouragement of the Congress in the state by its own central leaders continues.

One way to revive the party’s elan would be to make an informal alliance with the Aam Aadmi party which has been making steady, albeit limited inroads into mainly the disillusioned Congress vote in the cities of the state. In the October 2021 municipal elections it had secured an average of nearly 14% of the urban vote, with a maximum of 28.47% in Surat and 21.77% in Gandhinagar, at the centre of the BJP lion’s den. Surat, Rajkot and Gandhinagar account for 11.3 million of Gujarat’s population of 63 million. If Gandhinagar can be taken as a proxy for Ahmedabad, it comes to 17 million, i.e. 28% of Gujarat’s population. That could be the share of AAP’s vote in December, and most of it would have come from disillusioned Congress party voters.

An AAP-Congress alliance in Gujarat would therefore be a win-win for both parties, because it would not cause abstentions or a backlash vote in Congress for the BJP as has happened in UP and some other states. So it would virtually guarantee the defeat of the BJP in December.

Were the BJP to lose Gujarat it could cut Prime Minister Modi’s political legs at the knee. This could strengthen the disquiet in the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh over Modi’s blatant provocation of communal tension, that the RSS sarsanghchalak, Mohan Bhagwat has been voicing with growing stridency in the past more than two years. It would thus achieve in a single stroke what months of patient campaigning may not achieve – which is the cutting down of Modi to size within the Sangh Parivar, if not the outright defeat of the party in the 2024 elections.

If Kharge wishes to explore this possibility, it is he who must take the initiative in approaching Aam Aadmi Party, despite the latter being much the junior party. Chief Minister Kejriwal had approached the Congress three times before the 2017 Gujarat elections, offering not only to team up with the Congress but even to put up candidates chosen jointly by the two parties in the constituencies left to AAP. But he did not even receive the courtesy of an answer.

One result was that the Congress lost to the BJP in 18 constituencies with margins of 5,000 or fewer votes. In nine of these the margin of loss was fewer than 2,000 votes. Today, after another five years of disillusionment with a government that seems to cater only to the wishes of rich industrialists, the thirst for change is even greater. Gujarat may be ripe for change, but might vote for the BJP again for want of an alternative. The rise in the AAP’s popularity is a yardstick of this desire for change but Kejriwal and the leaders of AAP in Gujarat will not court such humiliation again, so the offer will have to come, this time, from the Congress.

https://thewire.in/politics/bharat-jodo-yatra-congress-new-beginning

Read More