“Kashmir came to India because we felt our ambitions and hopes would be fulfilled by allying ourselves with the great country which was India, which believed in democracy, in the rule of law… Now look at the treatment Kashmir has received… Let every Indian search his own heart.”

Sheikh Abdullah. Photo: File

This interview with Sheikh Abdullah was first published in the February 1968 edition of The Weekend Review, a supplement published by the Hindustan Times. The Wire is republishing it now because of the bearing it has on the ongoing debates in the Supreme Court and elsewhere over Kashmir’s constitutional status.

§

It is February, 1968. In a bungalow in New Delhi, the Lion of Kashmir Sheikh Mohammed Abdullah waits for the weather to moderate and the road to open so that he may return to his homeland. He waits also, with dwindling hope and increasing despondency, for some sign from the Union government that it is willing to give up its ostrich attitude on Kashmir. Today history is threatening to repeat itself. A carefully planned campaign seems to have been launched to rouse communal violence and then point to him as its cause. He has been falsely accused of having met the Chinese Charge d’ Affaires in the Pakistan High Commission. The ground is thus being prepared to force the government to put him away again as it did in 1963, in 1958, and in 1965. The Sheikh’s “sin” is that he is an uncompromising idealist in an era of political disillusionment. In this interview with Prem Shankar Jha of the Weekend Review, he sets out the political convictions that have sustained him in his long travail.

How were you first attracted to politics?

It was what I saw around me in Kashmir, I think, that first attracted me to politics – the distress, and the poverty which I saw as I grew up. As I have been telling my friends here (in Delhi), Kashmir, because of its natural beauty, has always attracted conquerors who have treated it as a prize a luxury item made simply for their enjoyment. They never thought of the Kashmiri people. This has been true of all conquerors including the Moghuls and most recently the Dogras. During all this time, the needs of the people were seldom looked after, and as I grew I found that poverty and illiteracy prevailed everywhere.

What led you to convert the Kashmir Muslim Conference into the National Conference in 1938?

You see, I was brought up in a place where I had the people of one community all around me, that is Muslims. Generally the Muslims are very much downtrodden in Kashmir. They are a huge majority – 95%. So naturally my first contact was with them and I was influenced by their distress and the injustices they suffered at the hands of officialdom. So I had the idea that they were suffering on account of their religion.

But later when I had had an opportunity to travel around and tour the whole state, I came across other people belonging to other religious communities – Hindus and Sikhs – receiving the same, and in places even worse, treatment than Muslims. So I came to the conclusion that the real fight was not between two religions, or two religious groups, but between “haves” and “have nots”, oppressed and oppressor. I found there were Muslims, there were Sikhs – people of all communities. So I began to feel that if one’s real purpose was to relieve oppression or distress, the best course was to serve not one group but all the people irrespective of caste, creed or colour. That was my reason for broad-basing the old Muslim Conference.

Was it when you found that the condition of oppression was not merely confined to Kashmir that you decided to join the States’ People’s Conference?

Yes, initially of course my views were formed by touring Kashmir state, but later when I went to Hyderabad, for example, I found the overwhelmingly Hindu population of that state in the same condition as the population of Kashmir.

When did you meet Mahatma Gandhi and Pandit Nehru, and what impression or impact did they create on you?

I met Panditji first when he visited Lahore and he was staying with Mian Iftikhar-ud-din Khan. I met him not at his house but at the railway station when he was proceeding to the (North West) frontier. It was 1938 or 1939. We had a talk at the railway station… I sat in his compartment…and accompanied him on his tour. Just like that. Just like that we had a long exchange of ideas. That was my first contact with him. At that time we discussed how to open the gates of the Muslim Conference to the other minorities in the state in Kashmir. We did not have to do (much) because the basic principles of the Muslim Conference were already universal and non-communal. So we had only to discuss the technical part of how to do it. We exchanged our ideas. I told him of my difficulties and he discussed the advantages of broad-basing the movement. So that was my first contact.

Gandhi’s impact on me was that he was a man of high principles and of noble, political ideals. He had a religious bent of mind. This attracted me to him ideologically. Another thing which impressed me was that he was a lover of truth. He would always stand by the truth. Once he was convinced that a certain thing was wrong it would not take him a minute to admit it. In his whole life he would not ask others to do anything which he himself would not practice first.

In 1945-46 Mr Jinnah came to Kashmir. What he was seeking at that time was to reconvert the National Conference into the Muslim Conference. Therein we naturally did not agree. But in Delhi when I met him I told him it was not my view only which matters, and that I would ask the advice of my colleagues. [I explained to him that] in 1931-32, we had gone through this debate and come to the conclusion that it was not merely a question of communities, and that it was the duty of every Muslim to fight to relieve the distress of everyone. We believed that this was the true Islam, so the Muslim Conference was opened to minorities. Unless I was convinced that this was wrong, I could not go back on this decision. I said that if my other colleagues decided unanimously to back to the original position, then I would not stand in the way. But in that case I would not be able to lead the Conference because personally I would still not be convinced. But I would accept the decision of my party because as a democratic principal if the majority decides, naturally I would then have to either follow or quit.

But finally no decision was needed. Mr Jinnah had come to Kashmir. He had accepted my decision. But there probably, he was advised not to accept my proposal to put his suggestion to the Conference because it was felt that I had so much influence with the working of the National Conference that they would always go by my advice. So he avoided referring the matter to the Conference. Naturally there was a conflict apparently after that his position was changed and he supported the Maharaja. His position as far as the princes were concerned was that the right to ‘decide the future’ affiliation was given to the princes and not the people. Therefore he stuck to that position, whilst the Indian Congress and the State Peoples Conference opposed his view point. They said that it was the right of the people to decide, and not of one man.

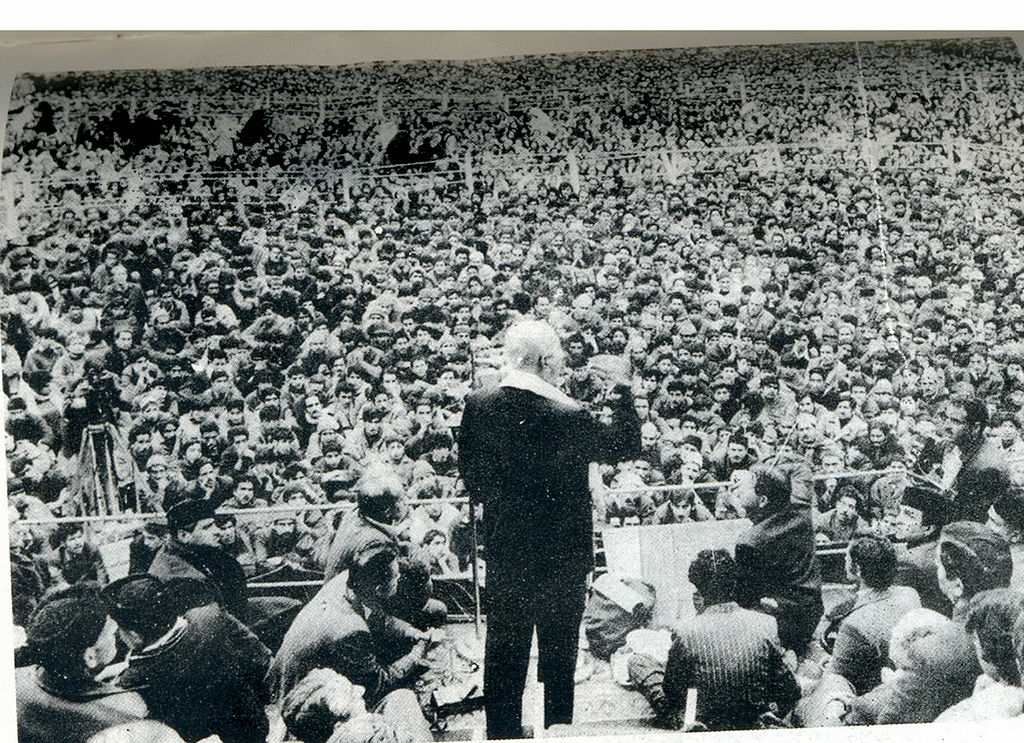

Sheikh Abdullah addressing a gathering at Lal Chowk in Srinagar in 1975. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

What was the situation in Kashmir in 1947?

Just before the emergency in 1947, I found anxiety all round, because of what was happening on both sides of Punjab. Thousands of refugees, both Hindus and Muslims, had poured into the state. They had suffered a lot and there was tension between the Hindus and Muslim of Kashmir. There was anxiety about what was going to happen. Then the Maharaja had not taken any decision about the accession. This was the main question that faced me on my release from jail on the 28th of September, 1947.

At my first public meeting which I addressed in Srinagar, I made my position on the accession clear. I felt that the people of Jammu and Kashmir were not in a position to take a decision at that moment because they did not know what shape, ultimately, the two dominions would take. There was so much trouble and nobody even knew whether the two dominions would exist. I suppose nobody knew whether the secular principle would survive at that time. Nobody knew what was going to happen. So we thought that this was not the time to take a decision which would influence not only us but also future generations. So we needed time.

That was one consideration. The second consideration was that we had been fighting since 1931 for a responsible government in Kashmir. We had not achieved that objective and the Maharaja was still an autocrat. We had to first gain our freedom before deciding about accession and we requested the heads of both the dominions, both Congress and the Muslim League, not to force us to take a decision at that moment, but to leave us alone.

I sent one of my colleagues Mr G.M. Sadiq, who is the present chief minister, to Lahore to meet the prime minister of Pakistan, Mr Liaquat Ali Khan and to put this question before him, but unfortunately they took the position that as the subcontinent was divided on the basis of Muslims and Hindus, and as Kashmir was a Muslim-majority area, it must ipso facto come to Pakistan. That position was not acceptable to us. Mr Sadiq told Pakistan that the decision must not be imposed on the people of Jammu and Kashmir but they should be given a chance to decide their own fate. Both India and Pakistan must accept (their) decision, whatever it may be. There was no agreement on that, so Sadiq returned and, soon after, the raids began and the picture changed.

When the raids began the Maharaja could not stop them because his forces were spread out throughout the state in small, batches. The raiders therefore nearly reached Srinagar, so he was advised (I don’t know by whom) and left in the dead of the night with his personal staff and belongings for Jammu; meanwhile he requested India for military support. India could not give this military support unless some legal basis was established. Lord Mountbatten advised his colleagues, Pandit Nehru and others that it would be wrong for India to send troops into a technically independent state. If India did so, Pakistan would do the same and there would be a clash between the two dominions, and since the army was still controlled by British personnel on both sides, it would be difficult for them to fight. So he suggested that some legal formula should be established.

The Maharaja was told that military help would come (legally) only if he signed the Instrument of Accession. Thus the Maharaja signed under duress, and in his letter whilst forwarding the document to Lord Mountbatten he stated clearly the circumstances under which he had signed the accession. Realising this position and the desire of the people of Kashmir for self-determination and their refusal to give up that position vis-à-vis Pakistan, the leaders of India accepted the accession provisionally subject to ratification by the people of Jammu and Kashmir at a later stage on the basis of a plebiscite. The condition of a plebiscite was laid [down] at that very hour.

Was it specifically plebiscite, or a ‘reference to the people’?

For that I would like you to see V.P. Menon’s book The Integration of the Indian States. He has devoted a chapter to each state and there is one on Kashmir too. He clearly says that because of these considerations the accession was ‘accepted subject to a plebiscite’. He has clearly used the word plebiscite in his book. Actually it was Lord Mountbatten in his letter to the Maharaja in which he accepted the deed of accession, who said this would become final after a “reference to the people” .

What were the problems you faced during the emergency government when you became prime minster?

My problems were multifold. Firstly there was a fear complex: Muslims were afraid of Hindus and Hindus were afraid of Muslims. In the Jammu and Kashmir state, Hindus would not think of going to Pakistan because of what had happened on that side. They thought they would be completely finished if the state acceded to Pakistan. The Muslims were afraid that if the state joined India then their fate would be the same as of Muslims in Kapurthala and other Punjab states. In India too, at that time, there were definitely two trends. One was the secular concept and the other trend was towards a theocratic concept. The Hindu Mahasabha and parts of the Congress and the general mass of the people also thought that if “they” have a Muslim state we must have a Hindu state. So (in Kashmir) we had to fight these trends. It was a tough fight and an uphill task for those who believed in humanity and not in Hindus, Muslims or Sikhs.

This was the problem facing us: how to create confidence in the two sectors in Kashmir. I thought that remaining in India on the basis of the Instrument of Accession was enough guarantee for the non-Muslims that their lives would be safeguarded and that their rights would be safeguarded. But how to create confidence amongst the Muslims. I thought that by guaranteeing an autonomous position (for) the state, they would have an assurance that there would be no interference with their internal affairs. As a majority, it would be up to them to provide safeguards for the minority and not vice versa.

Besides this, they would have the tremendous advantage of being a part of a country which claimed to be democratic and progressive, and in which the rule of law prevailed. By remaining a part of such a state, the condition and aspiration for which they had been fighting since 1931 would be fulfilled. So I thought that this would be a good compromise and I could retain the confidence of the people. Unfortunately communal forces and the trend in India which believed in a theocratic Hindu state proved to be too strong. And there was a break.

Sheikh Abdullah with other leaders of the 1931 agitation. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

You are referring to 1953? But you were very successful in doing so during the emergency (raiders’ invasion).

At that time there was imminent danger. In Kashmir, in spite of everything, people do not believe in violence and communal hatred. They belong to the same ethnic group. There are people, both Hindus and Muslims, who belong to the same caste and have the same surname – for example Bakshis are both Hindus and Muslim. Wattals are both Hindus and Muslims, and so on. So there was nothing that could separate them, and this helped us a lot.

What was the result you would have wanted to see emerge from a plebiscite?

At that time we thought that they could fulfil their ambitions by remaining a part of a democratic country in India because of Pandit Nehru and Gandhi and other Congressmen with whom we had close associations. We thought we too could remain a part of that country The sympathy of the Congress leaders for the people of Kashmir was fresh in the minds of the Kashmiris – how Nehru had suffered for them and Gandhi had sympathised with them. Though the ruler was a Hindu and a majority of the population was Muslim, this had not prevented the Congress leadership from identifying itself with the political movement in Kashmir led mainly by the Muslims. This had a tremendous impact on (Kashmiri) Muslims at that time. If a plebiscite had been conducted at that time, I am sure that it would have gone in favour of India. Later, of course, the situation changed, unfortunately.

Did the presence of the army create tensions?

From the very beginning we had to go through a lot of stress and strain even in 1947. When the first Indian Army troops came there, some of the battalions had completely lost their perspective. They thought that the fight was between Hindus and Muslims, no matter where the Muslim belonged to. We had to face this trouble [from the start]. A Sikh regiment from Patiala was stationed near the airport and wanted some volunteers. But the next morning when the camp moved out, we found the four volunteers dead in their bunkers. We had to face a terrible row in the city at that time. Then I called a conference and said that [the soldiers had perhaps] seen their nearest and dearest being killed in the riots. They were not in their normal mood as they thought that every Muslim was an enemy. They did not know that we were fighting for a certain cause. So we decided that the army heads and leaders must be told to inform the soldiers that they were fighting for an ideal. We did this and it had a very good effect.

During the period after the [Kashmir] war, how did reactionary forces, which you said earlier proved to be too strong, manifest themselves?

When we took over the administration, we had naturally to fulfil the promises we had made to the people for a long time about land reforms, the reduction and cancellation of debts, and other such reforms.

Landholdings were distributed among the tillers of the soil. Among the landlords there were Hindus, Muslims and others. But the Hindu landlords had a say in Delhi. They came here [to Delhi] and spread poison against us, trying to give the land reforms a communal colour. There were people here who readily believed these people. This vitiated the atmosphere of relations between Kashmir and the Centre, giving them a communal cast when the object of our reforms was purely economic.

Similarly with regard to debt cancellation. We passed a law according to which any debt in which the sum of interest payments had equalled or exceeded one and half times the value of the principal was considered automatically cancelled. Now, among the sahukars (moneylenders) also, there were both Hindus and Muslims. The Hindu sahukars were able, and did, complain to people here in Delhi, thus further vitiating the atmosphere. And then the Maharaja…we could not keep on the dynasty… When the dynasty was abolished, all those people who used to surround the Maharaja took advantage of this position, did not like the changes my government was making and combined to wage a campaign on communal lines in Delhi, in spite of the fact that none of the measures we had passed were communally motivated.

Was there any kind of discrimination in the allocation of jobs in Kashmir?

During my time there was none, but one thing was clear: with the spread of education, groups which were not previously represented began to claim jobs. So we had to satisfy their urges. Muslims, who were as you know a majority, had suffered for a long time and were nowhere represented in the administration. So naturally when they came up, they expected that they would also get their due. This is what happened in Hyderabad, where the Hindus came up in a similar manner. The position in Kashmir was exactly the reverse of Hyderabad.

My difficulty, however, was that I could not clean up the administration all at once. I could not remove people who had been working for years without providing them alternative employment. So, I was trying, little by little, to redress the balance of the various communities in government. The process was slow, but I can say with certainty that there was no discrimination.

One often hears in Delhi that you were arrested on the 8th of August, 1953 because you were on the verge of giving a unilateral call for independence. It is also said that you would have done so in your in speech on 1 August. I have read the text of the speech which you were to give and have not found anything to support this thesis. Was there anything else which could have led to this conclusion? Did you at any point even consider such a unilateral declaration could not happen? What was the dialogue you were engaged in with Panditji at the time of your arrest?

Panditji wanted the ratification of the accession by the Kashmir Constituent Assembly. I advised him that the world would not accept this situation, nor the people whom we had been assuring that theirs would be the final say. Actually I had suggested this course [ratification by the Assembly at an early stage] in 1950. At that time it was Panditji who had firmly refused to follow this course, saying that India was committed not only to the people but to the entire world to hold the plebiscite. This ratification was one of the purposes for which the Constituent Assembly had been called in 1950. But Pakistan and protested strongly to the Security Council, and India had assured the council twice through Sir Benegal Rao, who was the permanent representative to the UN, that India would abide by her commitments.

May I now come to the present day [1968], and ask you a few questions on which there has been some controversy recently: Firstly, quite a lot has been made in the press of your hesitation to declare your nationality as Indian. You subsequently clarified your position by saying that you were “provisionally” an Indian citizen, which did not really help very much. Would you care to tell me what made you hesitate to commit yourself?

The difficulty with me is that circumstances have drawn me into politics. Otherwise, I don’t feel myself good enough for this job. Because nowadays I feel a politician must know how to stab his friends. A politician must know all these dirty tricks. I find myself incapable of conspiracy, incapable of speaking untruths, and incapable of what we call diplomacy. I have suffered because of this.

With regard to this nationality question, in my press conference my main objection was to the attitude of the questioner. I felt that he was not asking this question with a good intention, Otherwise I would have explained the whole position then and there. And what I thought turned out to be true; this question was loaded, and was meant to spoil the atmosphere of the conference.

With regard to my nationality, I feel that this is the whole question under dispute since 1947. If the nationality of the people of Jammu and Kashmir is considered fixed once and for all, then there is no dispute left, and nothing to be settled.

But no one today seriously believes that there is no dispute. Even in 1965 when the war was going on, Vinobaji [Vinoba Bhave] is on record as having said that the Jammu and Kashmir dispute can only be considered truly settled when the people of India, the people of Kashmir, the people of Pakistan and the whole world agree that it is settled. So at the most, as far as I am concerned…you see, I have been a party to the provisional accession, so if you take it from a purely legalistic point of view then I consider myself as having accepted a provisional citizenship of Indian.

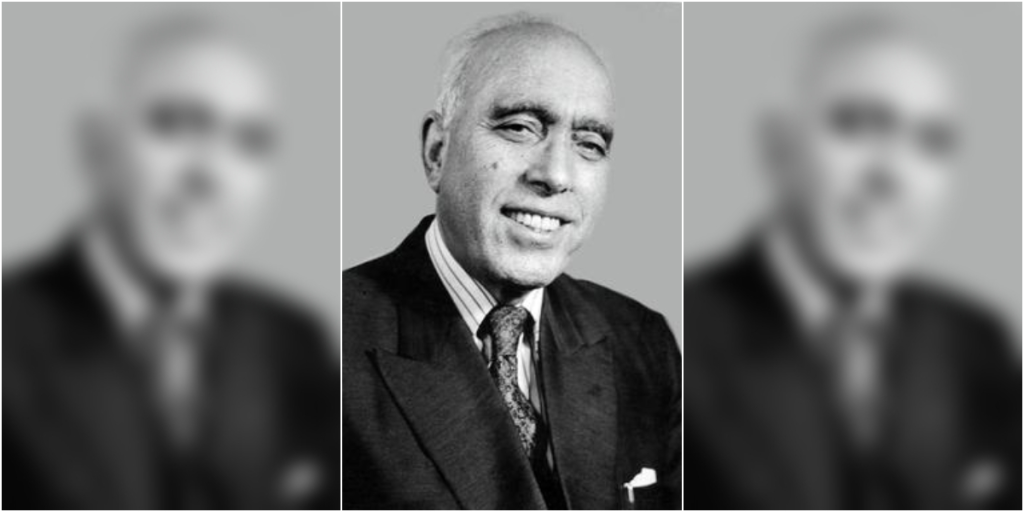

Sheikh Abdullah and Jawaharlal Nehru.

The second point is that we the people of Kashmir, of all shades, believe that so long as the uncertainty of the external situation continues, we can never have internal peace and stability. That has been our experience – not only mine but also of all my colleagues, including those who succeeded me. I have not been on the scene for the last 14 years, but all the material and moral help which the Government of India has given to Kashmir has not succeeded in bringing peace or stability. So we feel that peace and stability will only come when India and Pakistan come together, become friends. So the people of Kashmir have a self interest in seeing that India and Pakistan come together. I am working therefore for this purpose. So if you “fix” me, then where is the basis on which I can work for better relations? I must have a little freedom to negotiate.

‘The third point which I keep trying to explain to my friends in India is that in 1947, Kashmir did not come to India because of any pressure or persuasion, but of its own free will. It was because we felt that our ambitions and our hopes, for which we had made huge sacrifices since 1931, would be fulfilled by allying ourselves with the great country which was India, which believed in democracy, in the rule of law, which believed in equality of man. We believe in the high ideals which Mahatma Gandhi preached. Now look at the treatment Kashmir has received. That is an open book, and I don’t want to go into it. Let every Indian search his own heart.

But most people in Indian seem to think that the Kashmiris enjoy the same degree of democracy which Indians elsewhere do.

I wish Kashmir had that democratic constitution and that democratic way of life, but the fact remains that Indian democracy stops short at Pathankot. Between Pathankot and Banihal you may have some measure of democracy, but after Banihal there is none. What we have in Kashmir bears some of the worst characteristics of colonial rule. We are at the mercy of an ordinary police officer. Nobody can express his opinion freely. Let any Indian go there and honestly assess the entire situation. Can you blame Kashmiris for saying that when the Indian government has kept their leader, Sheikh Mohammed Abdullah, in jail for 14 years without a charge, what can they expect from it in the future in the way of fair play?

We did not come [accede] to Indian because of its vastness, or because it is a moneyed country. We were enamoured of the high principles for which you stood. But today, let alone what is happening in Kashmir, even here I have been released but I am discouraged from speaking of my cause. What happened in Meerut? The chief minister of UP directed all his district magistrates to prevent me from speaking if he felt this would lead to disturbances. The chief minister did not bother to find out who were the troublemakers in Meerut. What did I say at that public meeting? I delivered an address of nearly two and a half hours. The speech is there. I could be taken to task on the basis of that speech, but even there in Meerut when the atmosphere was so tense, I preached communal harmony. Does it become a minister in a democratic country to take such an attitude? Now I am warned not to go here, not to go there, not to go there…this how Indian democracy functions. How do you expect the people of Kashmir today to come rushing to you?

Of course India can keep Kashmir by force. But this way it will have the bodies of the Kashmiris but not their souls. That would not be a true accession. Accession should be of minds and hearts, and love and justice are the only two weapons which come with you for that accession.

In your public meetings and your talks, have you found the people more responsive to your suggestions than before?

As far as the common people are concerned, I have found them very responsive. They understand things, they are themselves tired of these people who exploit them, who try to exploit their emotions. There is a good response from the people. It is only gangs of assassins, who have learnt the art of murder, who have been taught how to stab people. These people hide in a bush and when a person is walking unawares, come up behind him, stab him, and run away. But not a single man has been caught, although in Meerut nearly 30 people have been stabbed.

There have been disturbances in many places – Rourkela, Ranchi, even Srinagar. Hundreds of people have been involved, but no one has been hanged for murder committed during communal disturbances. I know very well that this is not representative of what is happening in the whole of India, and that India is a vast country, but these things are happening, and they have a terrible effect on the people of Kashmir.

We had some Kashmiri students studying in Ranchi in the medical college there. They returned home almost naked. When they reached their home, they narrated their tale of misery and woe to the people. How could these things not effect the listeners, and how could you expect them to look to India for protection? These things have got to stop, but they will never stop until the tension between India and Pakistan is resolved. There is only one answer to this problem and that is to end the strife on the subcontinent. How long can this be avoided?

This interview was originally published on February 17, 1968 in the Weekend Review and is republished here courtesy the Hindustan Times.

Read More