Imposing embargoes on trade with Russia and punishing those who ignore them by cutting off their international banking facilities will only force uninvolved nations into rival militarised camps.

The Indian government’s stance on the Ukraine war is the first time that a genuine consensus of opinion has emerged between the Narendra Modi government and the opposition in our increasingly divided country. Indian opinion is united that Russia’s decision to invade Ukraine without first bringing its anxiety about what was happening to ethnic Russians in the Donbas region to international attention, and without raising its concerns on any of the platforms provided by the United Nations, was a serious mistake. But it is also united in believing that the road back to peace does not lie in the blanket condemnation of Russia, in the blanket denial of every single explanation that Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov has given for its resort to force, and in ascribing it to a power-crazed Russian president who has lost touch with reality.

Nor does it lie in sanctions that will cripple not only the Russian economy but also hurt the economies of Western Europe and the rest of the world. Finally, and most importantly, India is rightly angered by the US’s barely veiled threat that these sanctions will be extended to other nations that do not fall in line with US sanctions despite the fact that these have no UN mandate behind them.

The US has been ‘punishing’ errant nations that have dared to buy oil from Iran in this way through financial sanctions for some time. But Russia is not Iran. Nor is natural gas its sole export. On the contrary, Russia exports a large quantity of coal, oil, semi-finished iron and raw materials ranging from timber to aluminium, nickel, cobalt and gold to the rest of the world. Imposing embargoes on trade with it and punishing those who ignore them by cutting off their international banking facilities or freezing their reserves will only force uninvolved nations into rival militarised camps. That will push the world towards a war that it can no longer afford.

This is not an alarmist statement, but a reminder of what has happened once already within living memory. On July 2, 1940, US president Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed the US Export Control Act, which authorised an American president to license or prohibit the export of “essential defence materials” to potentially hostile countries. At the top of that list was Japan.

Between then and July 26, these sanctions were applied to an ever-widening range of metals used in the manufacture of weapons and, significantly, to aviation fuel. Nor did the embargo stop there. On July 26, 1941, Roosevelt froze all Japanese assets and bank accounts in the US. Since Japan imported nearly all of its oil from the US, this amounted to strangulation by degrees, especially of its military. A diary belonging to one of Emperor Hirohito’s aides, discovered in the early 2000s, revealed how the Japanese viewed this devastating blow: It quoted the late emperor as saying that Japan went to war with the US because of oil – and lost the war because of oil.

In short, the freezing of Japanese assets left the Emperor with no option but to sanction the invasion of Indonesia and Indo-China in pursuit of oil. The embargo also led to Japan joining Germany’s Tripartite alliance in 1941, and thence to the attack on Pearl Harbour in December 1941.

A similar gravitation of countries into two potentially hostile groups has begun now. One is forming around the US and NATO; the other is beginning to take shape around Russia, China and Iran. An alarming feature of this development, were it to continue, would be that it will end by disrupting not just the unified global trade and manufacturing systems of the world, but the global payments system as well. This will set off a race to create a second, alternative payments system. And with China’s foreign exchange reserves being close to $4 trillion, the base for creating an alternative payments system already exists.

Were a Yuan-centred alternative payments system to emerge, the shift of a portion of global financial reserves from the dollar, Pound, Euro and Yen could lead to a steep fall in their value. The consequences of such a shift are not easy to estimate but the possibility that it could trigger a ruinous war should not be discounted.

Drift towards armageddon

This drift towards armageddon can only be arrested if the West ends its no holds barred effort to pin all the blame for the present situation in Ukraine upon Russia, and upon Vladimir Putin in particular. But how can it even begin to do this after blocking every media channel emanating from Russia except its own?

The West’s justification for strangling Russia’s voice is that, having already started the war, it has no option but to lie about it now. This may well be true, but does that give the Western countries the right to deny their own people the freedom to hear their opponents and come to their own conclusions? And has it not occurred to the decision-makers in NATO that their denial of this right exposes the hollowness of their own commitment to democracy?

There can be no meaningful dialogue between nations without a minimum of mutual respect and a willingness to listen. That is precisely what the US and every European government have decided to deny to Russia and to their own people from day one of the invasion of Ukraine.

So what can civil society do to limit its loss of perspective on the Ukraine war? The answer is that we must try to piece together the information we already have to arrive at our own conclusions about Russia’s motives.

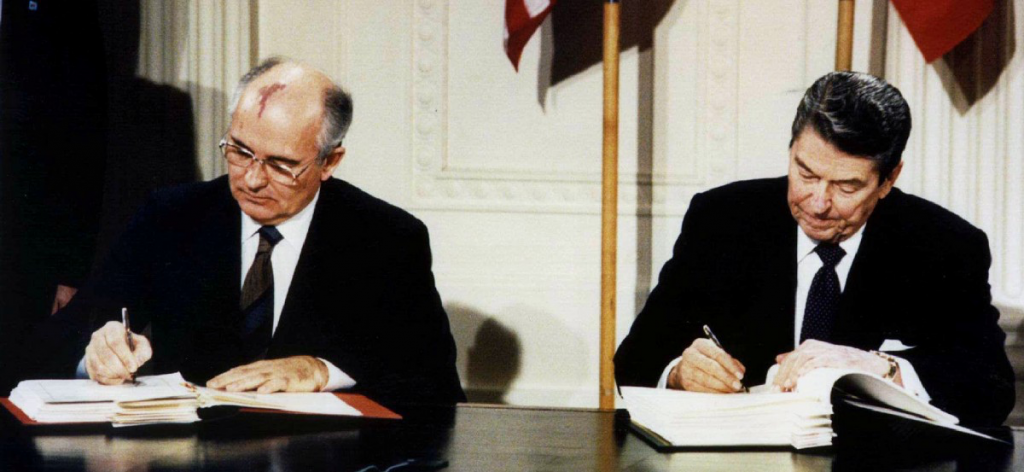

The starting point of this exercise is to remember how the Cold War came to an end. The crucial breakthrough was made by US president Ronald Reagan and Soviet president Mikhail Gorbachev at Reykjavik, Iceland in 1986. It was given concrete shape in a series of follow-up meetings that ended in the signing of the Budapest Memorandum of 1994.

The understanding between Reagan and Gorbachev that ended the Cold War was based on the decision to remove intermediate range missiles, dismantle strategic missiles and nuclear warheads, and retain only enough highly enriched uranium for a limited number of nuclear warheads. Both knew that once this was done, the Cold War would, in effect, be over. The creation of a buffer zone of neutral states between the USSR and NATO did not come up at Reykjavik because no one there anticipated the suddenness of the economic and political collapse of the Soviet Union and the dissolution of Warsaw Pact. Consequently, no government in the West anticipated the suddenness with which NATO would find itself without an enemy and therefore without a job. All the problems in the maintenance of a stable peace that have plagued intra-European relations since then have their roots in the suddenness of that collapse.

The speed with which it happened created a succession of challenges that no one at Reykjavik had foreseen. The first arose with the fall of the Berlin wall and the reunification of Germany in 1989. To allay the Soviet Union’s fear that this would allow NATO troops and armaments to be stationed at the very edge of the Warsaw Pact countries, on February 9, 1990, US Secretary of State James Baker assured the Kremlin that NATO would not expand ‘one inch eastward’.

While this remark by Baker has been widely reported, and frequently dismissed as a mere oral reassurance with no legal sanction, what has only recently come to light is that just three months later, in an extensive set of talks with Gorbachev designed to prepare the ground for the summit meeting between him and US president George H.W. Bush in Washington, Baker gave Gorbachev nine assurances that there would be a change in the character of NATO from a military to a political alliance that would not be threatening to Moscow.

Baker’s aim was to allay Soviet fears arising out of Germany’s reunification, by offering the assurance that neither NATO command structures nor NATO troops would be transferred to the territory of the former East Germany. Realising that this assurance would make it difficult to apply NATO security guarantees (especially Article 5 which states that an attack on one member will amount to an attack on all the members of the organisation) to the whole of Germany, Bush also suggested to Chancellor Helmut Kohl that he should, in the future, speak of a ‘special military status’ for East Germany.

The next, larger challenge came with the disintegration of the Soviet Union, the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact and the plunge of Russia into abject poverty. The mere fact that Baker and H.W Bush had gone as far as they had to reassure the Soviet Union meant that they had tacitly, if not explicitly, accepted the Soviet pre-condition that the countries around its periphery should not become a part of NATO. But now, with the Soviet Union itself having disintegrated, it became fatally tempting for hawks in the US to argue that commitments made to the USSR did not necessarily apply to Russia.

But Russia had one more bargaining chip – the West’s need to disarm the colossal stock of nuclear warheads that had developed during the Cold War. Dismantling these in Ukraine was especially important because it contained the launch sites of 1,900 missiles with mammoth warheads. This was achieved in 1994 with the signing of the Budapest Memorandum on Security Assurances. In that conference, the US Secretary of State gave another oral assurance that NATO would not expand eastwards towards Russia’s borders. This paved the way for Russia to dismantle its formidable nuclear arsenal in Ukraine, in exchange for aid in rebuilding its economy.

Had successor governments in the US honoured their oral commitments, Europe would have had lasting peace now for more than 30 years. But for NATO, the temptation to fill the vacuum created by the collapse of the Russian economy proved too strong to resist. So NATO continued to expand. At the end of the Cold War, it had 16 members, four more than when it was created. The new entrants were Greece, Turkey, Germany and Spain, all of which were inducted in the 1950s and 60s, at the height of the Cold War.

But in the 1990s, even after the break-up of the Soviet Union and the immiseration of Russia had eliminated any conceivable threat from it to Europe, NATO continued to add new members. By 1999, it had added Hungary, Poland and the Czech Republic, all border states of the former Soviet Union. What is more significant – these countries joined NATO at its invitation.

After 1999, NATO cast all restraint to the winds and declared an “Open Door” policy for other countries to join it, provided they met its preconditions for entry. Russia protested against this relentless expansion four times, in 1993, 1997, 2007 and finally when NATO was wooing Ukraine, in 2012. Then in 2014, when it appeared that Ukraine would be the next to join NATO, and would demand the vacation of its Black Sea naval base at Sevastopol, it invaded and annexed Crimea.

The US reacted with predictable fury, emphasising Russia’s violation of international law, and imposing a whole string of sanctions upon it that were designed to bring its economy to its knees. But it carefully chose to forget that Crimea had been an integral part of Russia, not Ukraine, for centuries; that Russia had beaten off a British invasion of the peninsula in 1853-56, and that Moscow had attached Crimea to Ukraine for reasons of administrative convenience as recently as in 1954, when Ukraine was a part of the Soviet Union. It also chose to ignore the fact that 65% of Crimeans were ethnic Russians and only 15% were Ukrainians.

Finally and most dangerously, the Barack Obama administration ignored warnings by former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and university of Chicago professor John Mearsheimer to leave Ukraine alone.

In the Washington Post on March 5, 2014, Henry Kissinger wrote: “The test of policy is how it ends, not how it begins. Far too often the Ukrainian issue is posed as a showdown: whether Ukraine joins the East or the West. But if Ukraine is to survive and thrive, it must not be either side’s outpost against the other — it should function as a bridge between them.” [Emphasis supplied]

Mearsheimer, who gave a 60-minute talk at the University of Chicago in June 2015, also stated without equivocation that the responsibility for creating a confrontation with Russia rested entirely upon the West. Behind its sanctimonious talk about defending ‘orange’, (i.e democratic) revolutions lay a single-minded desire to peel Ukraine away from Russia, and to expand NATO relentlessly till it completely encircled Russia in the west.

Thirty years of disrespect and broken promises by NATO and its member states help to explain why Putin finally lost patience with the West and decided to use force to bring Ukraine to its senses. But it does not explain either the timing of the attack or the justification he has given – that it was to stop a surreptitious ethnic cleansing of Russians from the Donbas region, towards which the Ukrainian government had been turning a blind eye ever since the annexation of Crimea.

Ukraine and Neo-Nazis

The Western media, prepped no doubt by their foreign office spokespersons, have simply ignored, or trashed, these allegations. But could there be any truth in them? An examination of Ukraine’s politics suggests that while Moscow may be exaggerating the extent of ethnic cleansing that has occurred, the possibility that there has been an attempt by irregular forces to ‘cleanse’ the Donbas of ethnic Russians cannot be ruled out. For, nearly 80 years after the death of Hitler, xenophobic Fascism is alive and flourishing in western Ukraine.

This became starkly clear when, in Ukraine’s parliamentary elections of 2012, Svoboda, a right-wing, fascist party, which is a throwback to the 1930s and is based entirely in western Ukraine, garnered 10% of the vote, and sent 37 members to the parliament. Svoboda’s leader is Oleh Tyahnybok, whose battle cry has been the “liberation” of his country from the “Muscovite-Jewish mafia”.

Tyhahnybok is not all hot air, for he practices what he preaches. In 2010, two years before entering parliament, he rushed to Germany after the conviction of the Ukrainian Nazi death camp guard John Demjanjuk for his role in the extermination of nearly 30,000 people at the Sobibor camp during World War II to declare him a hero who was “fighting for truth”.

His deputy, Yuriy Mykhalchyshyn, is an even more unrepentant Nazi: Not only is he fond of quoting Joseph Goebbels, but he founded a think tank originally called “the Joseph Goebbels Political Research Center.” According to Per Anders Rudling, a leading academic expert on European neo-fascism, the self-described “socialist nationalist” Mykhalchyshyn is the main link between Svoboda’s official wing and neo-Nazi militias like Right Sector.

Had Svoboda continued its run of success in the 2014 and 2019 parliamentary elections it is possible that it would have become more moderate over time. But it went in the opposite direction so its success did not last. In the 2014 elections, its share of the vote plummeted 4.71% and it lost 31 of the 37 seats it had won two years earlier. In 2019, its vote fell further to a mere 2.15% and it won just one seat. But its leadership did not change. So it is entirely possible that its more ultra-nationalist members have drifted right and further strengthened their links with the Neo-Nazi militias.

This may be the genesis of the attacks on ethnic Russians in the Donbas region that have seemingly pushed Putin over the brink and into war. For what is certain is that neither President Volodomyr Zelenskyy, nor his Servants Of The People party, which is made up largely of workers and ex-communists, and had won an unprecedented absolute majority in parliament in 2019, had any need to resort to such tactics to shore up their popularity.

Putin’s advisers must know that in Zelenskyy, whose grandfather was a general in the Soviet Army during World War II, they have a Ukrainian president who is not only likely to be more receptive to his complaints but also more wary of NATO’s blandishments. That is why his invasion of Ukraine without first exploring the possibility of direct talks with Zelensky needs to be seen, above all, as a strategic blunder. For it has weakened the one man in the one Ukrainian government with whom he could have found common ground onto which to guide their relations in the future.

Read More