The prime minister is spending almost 11 times as much on meeting the same need as the Delhi chief minister. Is that because his job is 11 times as onerous as a chief minister’s? Or is it because Modi’s ego is considerably larger than Kejriwal’s?

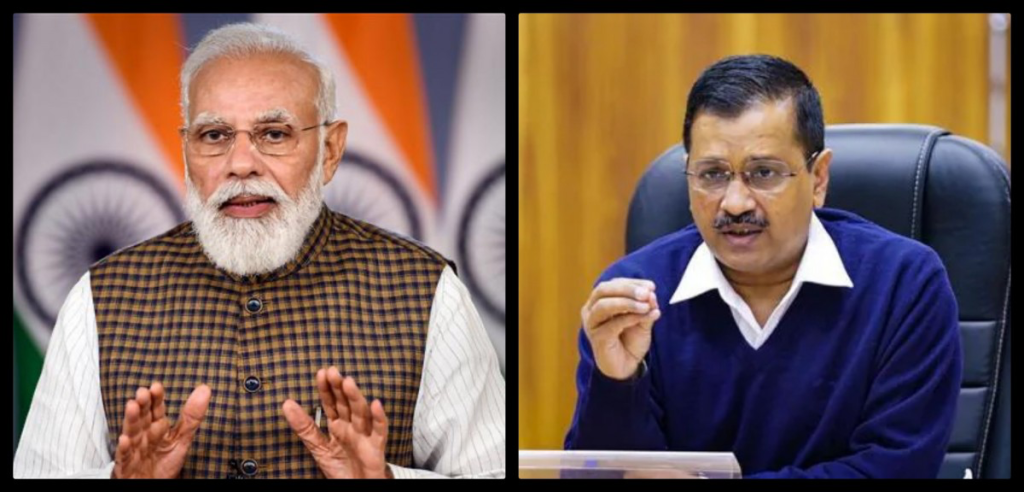

Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Delhi chief minister Arvind Kejriwal. Photos: PTI

Narendra Modi must be in seventh heaven. His bete noire, potentially his nemesis, Arvind Kejriwal has been found to have feet of clay. For years now, Kejriwal has tirelessly contrasted his own simple lifestyle, and his party’s serving of people, with Modi’s endless preoccupation with himself, and exclusive concern for the industrial health of the super rich, such as the Ambanis, the Adanis and the Tatas.

Ten days ago, Kejriwal had used the one weapon against Modi that a dictator has no defence against: satire and ridicule. Charlie Chaplin, the greatest comedian of the 20th century, had used this against Adolf Hitler in his immortal 1939 film, The Great Dictator. Kejriwal had done this ten days ago with a 20 minute story he narrated in the Vidhan Sabha, titled “Chauthi Pass Raja”. This was having the same effect in India as The Great Dictator had had in the US: videos of the story have garnered millions of views. The release of data to show that the CM’s house his government is building costs Rs 45 crore was Modi’s counterattack!

But will it succeed in denting Kejriwal’s hold on the people of Delhi? The commercial media’s gleeful acceptance of the estimate as gross extravagance by a man whose ego has finally outstripped his unremarkable physical stature, was only to be expected in a country where investigative journalism has been strangled to death. But surely, some newspaper needed to contrast that story with the cost of Modi’s own pet project, the Central Vista Redevelopment project, which is Rs 13,450 crore, i.e $1.7 billion.

This redevelopment is to spread over 20,866 square metres and have a total built up area of 64,500 square metres. Within it the prime minister’s house complex will cover 36,268 sq ft (more than 4,000 square metres) and cost Rs 467 crore. This is more than ten times the amount estimated for the Delhi chief minister’s proposed housing complex.

The prime minister’s new office and residence will be on a site covering 15 acres. It will contain ten four-storey buildings that will accommodate not only his residence, but the living quarters of his Special Protection Group and his private office complex.

This is no different from the present arrangement in (the former) Race Course road where these functions are spread over 4 buildings set in lawns that cover approximately 16 acres. This arrangement has comfortably served five previous prime ministers from Rajiv Gandhi to Manmohan Singh.

Despite that, Modi’s reasons for the complex closer to Parliament House and the prime minister’s official secretariat are understandable, because of the rapidly increasing traffic on New Delhi roads, the worsening traffic jams being caused by it, and therefore the increasing vulnerability of any cavalcade to a terrorist attack.

Construction for the Central Vista project. Photo: Oishika Neogi

What necessitated reconstruction of CM residence?

But these same considerations, multiplied many times, were what necessitated the reconstruction of the chief minister’s residence. For Kejriwal had categorically refused to move into Raj Nivas, the residence of the British chief administrators of Delhi, and later of chief ministers after Delhi became a state, pronouncing it too grand and too large for him and had, instead, chosen to stay at what used to be the Delhi Vidhan Sabha speaker’s residence at 6, Flagstaff road in old Delhi.

All those who met Kejriwal at home in those days will remember that 6, Flagstaff Road is a single floor house with a small front lobby that Kejriwal had turned into an informal meeting room, a central living and dining room, and three bedrooms spread around it, one of which was occupied by his father and a computer. That was all!

The entire house reeked of dilapidation. Considering that it had been built in 1942, barely a decade after the British shifted their capital from Calcutta to Delhi, this was hardly surprising. So, having lived in a similar house in New Delhi, in the 1950s and 1960s, I was not surprised to learn that the ceilings of all the three bedrooms had begun to leak.

Those who are accusing Kejriwal of having been corrupted by power today, need to ask themselves why this surfaced only in 2020, seven years after AAP first came to power in Delhi? The short answer is that when he chose 6, Flagstaff Road over Raj Nivas, Kejriwal did not realise that the chief minister’s house needed to serve also as his main office.

This had been understood by the British as far back as in 1906, when they built the first office-cum-residence Raj Nivas on what was then the Ludlow Castle Road, and is now the Raj Nivas Marg.

After Independence, with an ever-expanding city and increasing state regulation of civic life, this complex became too small by 1988. Both wings of Raj Nivas where therefore completely redesigned and expanded into a residence-cum-secretariat at great expense in 1995.

This background is necessary to understand why the conversion of 6, Flagstaff road from being simply one chief minister’s choice of a home, into the official residence of all future chief ministers of the state is costing Rs 45 crore. Kejriwal had chosen it as an unpretentious home to live in. But a chief minister’s home can never be private. On the contrary it has, necessarily to be a mini-secretariat that can receive information and transmit decisions instantly, as and when the chief minister needs it to do so.

In 2015, when Kejriwal chose to live there, it was a home without an office. In the next five years this lacuna was filled by the ad hoc addition of temporary rooms constructed between the gate and the entrance to the house. These sufficed till 2020, when the COVID-19 lockdown was imposed. The shut down of the entire Delhi secretariat did not lead to shut down of work. On the contrary, with the need to open COVID wards, arrange medication, oxygen and ambulances, and look after tens of thousands of migrant workers suddenly rendered destitute, 6, Flagstaff road suddenly became the pulsing nerve centre of government.

I cannot even begin to imagine how his administration coped with the crisis from the ramshackle bunch of huts I had seen at Flagstaff road. But that experience, without a doubt, taught Kejriwal a hard lesson: he had to choose between looking and acting like a leader of the poor ever in search of votes, and a leader who wished to deliver service to the poor and save their lives. It is not therefore surprising that the first order for refurbishings worth Rs 7.09 crore, was issued on September 09, 2020.

Once it was decided that 6, Flagstaff Road would be the permanent official residence of the chief minister of Delhi, another need arose that had been largely overlooked in Kejriwal’s first years. His was for quarters for his personal security staff. It was this need that had caused the present official prime minister’s residence to expand from 5, Race Course road as his home and 7, Race Course Road as his personal office, to include 3 and 9 Race Course Road as well.

It is also the need explicitly stated for the PM’s residential complex Modi is setting up on the edge of the Central Vista lawns. Modi is therefore spending almost 11 times as much on meeting the same need as Kejriwal. Is that because the prime minster’s job is 11 times as onerous as a chief minister’s? Or is it because Modi’s ego is considerably larger than Kejriwal’s?

Read More