If there is a lesson the opposition needs to learn from Modi’s endorsement of a film that he has almost certainly not even seen the trailer of, it is that he will stop at absolutely nothing to come back to power in 2024.

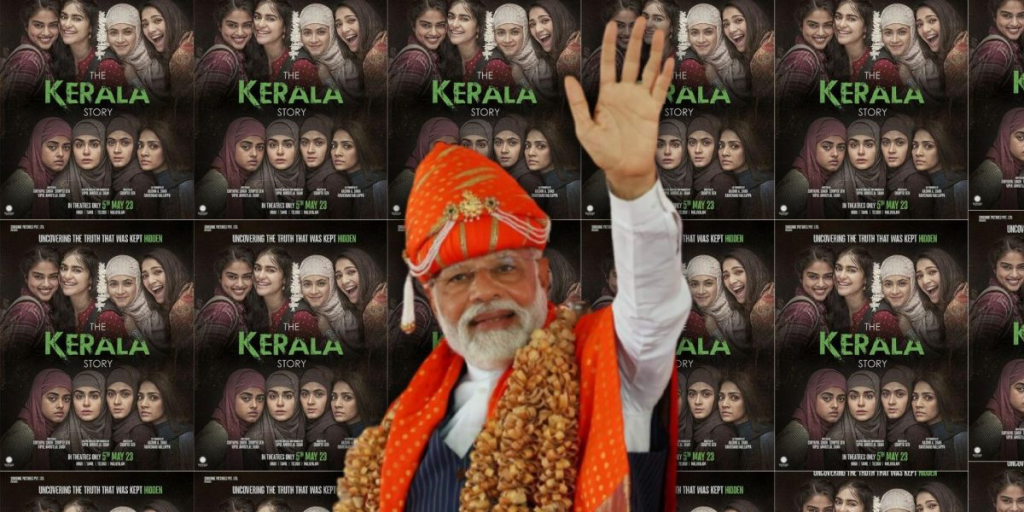

PM Modi. In the background are posters of ‘The Kerala Story’. Photos: Twitter/@BJP4Karnataka and IMDb.

Barely a year after the release of The Kashmir Files, Prime Minister Narendra Modi is again using another grossly incendiary film, The Kerala Story, to fan hatred of Indian Muslims in order to consolidate the “Hindu” vote and stay in power next year.

The Kashmir Files was a hugely distorted and highly inflammatory depiction of the planned murders of prominent Kashmiri Pandits in the early months of 1990, which was designed to ethnically cleanse the valley of its Pandit community. The Kerala Story accuses Muslim organisations in Kerala of supplying 32,000 recruits to ISIS, the self-styled Islamic State terror group which briefly established control of territory in Syria and Iraq. Many of these, it claims, were women recruited to serve as the wives of IS fighters.

The brazen disregard for the truth displayed by both films reflects how completely the Bharatiya Janata Party, under Modi, has become a conduit for lies. For, one brief look at the actual Kashmir files – not the screen version but the Union home ministry’s papers – would reveal that the killing of selected Pandits in 1990 was planned and paid for, in weapons and cash, by the Pakistan army’s Inter Services Intelligence (ISI) and carried out by a handful of self-styled mujahideen recruited by it from among the many thousand young Kashmiris who had joined the rebellion against India after the Gaukadal police firing upon civilians in Srinagar in January 1990 that took between 24 and 55 lives.

How opposed the average Kashmiri Muslim was to becoming a part of Pakistan, even after the 14 years insurgency of insurgency and draconian repression that followed, was revealed by two international opinion polls carried out in 2004 and 2009 . The first was conducted by MORI, Europe’s premier sampling survey organisation, and the second jointly by MORI with GALLUP. The 2004 poll showed that 61% of the population of Jammu, Kashmir and Ladakh wanted to remain a part of India and only 6% preferred Pakistan.

Similarly, the 2009 poll, which was initiated by Chatham House, Britain’s premier foreign policy think tank, and confined to the Kashmir valley, showed that even in the four worst-affected districts of the valley, only 2.5 to 7.5% of those surveyed preferred Pakistan to India.

That was the strength of the bond between Kashmiri Muslims and secular India that Modi fatally weakened within weeks of coming to power by breaking off all talks with the Hurriyat Conference, unleashing a reign of terror in the valley, gutting Article 370 of the constitution, and turning Jammu and Kashmir into a Union territory, thereby disempowering Kashmiris within their own state. That is the bond that The Kashmir Files has weakened further by creating alienation not in Kashmir but in the Hindu population of the rest of India.

The Kerala Story is intended to do the same to the 1200 year-old bond between the Hindus, Christians and Muslims of Kerala. It is a measure of Prime Minister Modi’s insecurity about his party’s – and his own – future that he is now openly endorsing the grotesque lie cooked up by his bhakts and his propaganda machine that there was an exodus of Muslims from Kerala to join Daesh, the Islamic State in Syria and Iraq.

Here is what Modi said in a pre-poll speech at Ballari in Karnataka, on May 5:

“ In these changing times, the nature of terrorism is also changing …Bombs, rifles and pistols… (have been replaced by) a new type which undermines society from within, makes no sound. The Kerala Story is a film based on one such conspiracy in Kerala”.

What is the theme of The Kerala Story that Modi is asking the people of Karnataka and the rest of India to treat as gospel? It is that Muslim organisations in Kerala supplied 32,000 recruits to ISIS when it established its brief, blood -soaked control of territory around Raqqa, Deir-ez-Zor and Mosul in Syria and Iraq. Many of these, it claims, were sent to serve as wives for the IS fighters.

What is far more incendiary, the film depicts in graphic detail how many of them were Hindu girls who had been converted to Islam before being inveigled into going.

Several reviewers, who did not bother to do the 30 minutes of research on the internet that has gone into the writing of this article, have stated that this is “a serious issue lost to bad direction, and worse writing” (India Today). The Organiser, the de facto mouthpiece of the Rashtriya Swayamsewak Sangh, has described the film as “a dangerous truth told with a calculated balance”.

But the entire film is such a bald-faced lie that to find the prime minister of India mouthing its praise and endorsing its contents in a public speech brings shame upon the entire country. Study after study, both in India and abroad, has noted the almost complete absence of Indian Muslims in the ranks of the IS. On December 20, 2017, Hansraj Gangaram Ahir, Modi’s minister of state for home affairs in his first stint as PM, reported to the Rajya Sabha that only 103 people who “sympathised” with ISIS had been arrested across 14 states by the National Investigation Agency (NIA), according to the data available with the government. The minister added: “Very few individuals [from India] have come to the notice of the central and state security agencies who (sic) have joined ISIS.”

Uttar Pradesh – India’s most populous state – reported a paltry 17 sympathisers, followed by Maharashtra (16), and Telangana (16). Kerala had reported only 14 and Karnataka a mere 8. What is more, these were individuals accused of being ’sympathisers’ – and who had not left India to join ISIS in the desert.

Two years later, at the start of Modi’s second term in June 2019, minister of state for home Affairs G. Kishan Reddy stated in a written reply to Lok Sabha that the NIA and state police forces had registered cases against ISIS operatives as sympathisers, and have arrested 155 accused from across the country.

Three years later, in a detailed study published by the Manohar Parrikar Institute of Defence Studies and Analysis at New Delhi, Adil Rasheed reported that until 2019 less than 100 migrants working in the Gulf were thought to have been lured into ISIS while 155 had been arrested in India for having ISIS links.

“The mystery behind the very few Indian names appearing in the long list of foreign fighters in the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS),” he wrote, “has puzzled strategic thinkers for some time now. This pleasant yet inexplicable surprise finds a historical precedent in the conspicuous absence of Indians from the legions of foreign ‘mujahideen’ fighting the Soviet occupation in Afghanistan in the 1980s and from the Taliban and al Qaeda’s ‘Islamic Emirate’ of the 1990s”.

The figure of 32,000 recruits from India, and the assertion that a large number of them were women, is therefore absurd – all the more so because estimates by the European Union and the Central Intelligence Agency in the US have put the maximum strength of the IS at its height at around 30,000.

What is more, 5,000 of them had been recruited in Europe and most of the remainder had come from Arab countries devastated by civil war after the so-called Arab Spring. The largest number had come from Libya, whose economy had been totally destroyed by the concerted Euro-American attack upon it in 2011. The idea that 32,000 Indian Muslims had also joined IS, whether as fighters or sex slaves, is therefore ludicrous.

That Modi, speaking in Hindi, should have gone to the length of endorsing such a dangerously incendiary film at Ballari in Karnataka before a large crowd whose grasp of the language is poor to non-existent, reveals that his intended audience was not Kannadigas, but the vastly larger masses of unemployed and desperate youth in the Hindi-speaking belt. These are the young Indians to whom he has so far been unable to provide jobs and a secure future, and who are now being primed to attack Muslims in order to retain their support for the BJP in the 2024 general election.

If there is a lesson the opposition needs to learn from Modi’s endorsement of a film that he has almost certainly not even seen the trailer of, it is that he will stop at absolutely nothing to come back to power in 2024 and is willing to plunge the country into communal violence, not to mention war with a nuclear armed neighbour, if that is what it will take. This is what has transformed the role of the opposition in the next general election from one of winning the maximum number of seats to saving India from disintegrating in a sea of blood.

It is, therefore, imperative that they put aside their political rivalries with each other and unite to meet the threat to India’s very existence that the BJP under Modi and Shah now poses to India’s very existence. The leaders of all the major opposition parties, including the Congress, are now fully aware of this. But, as the no-holds-barred struggle between Sachin Pilot and Ashok Gehlot in Rajasthan, and AICC general secretary and former Delhi Congress party chief Ajay Maken’s incessant diatribes against the Aam Admi Party have shown, this realisation has yet to trickle down into the second rung of the Congress party’s leadership.

The resistance at this level is understandable, for these are the leaders who manage party cadres at the ground level, and the surrender of some seats to other parties inevitably leads to demoralisation and defections of cadres in those constituencies. All opposition parties, and particularly the Congress, face this problem, but there is a solution to it.

This is for the opposition to agree to confine coalition building to the Lok Sabha elections and continue to fight each other in the Vidhan Sabha elections. This would not have been possible earlier, when Lok Sabha and Vidhan Sabha elections were held more or less simultaneously – as used to happen till the 1960s – but today presents no major problem.

By concentrating entirely upon national and international issues in his relentless campaigning during the past nine years, Modi has made it possible for the opposition to do the same. If it comes to an agreement over this, its victory in 2024 will be assured.

Read More