What is important is for the opposition to convey to the public that in the battle to defeat Modi’s BJP in 2024, the differences between Congress and AAP signify nothing.

Arvind Kejriwal (L) and Rahul Gandhi. Photos: Official Twitter handles

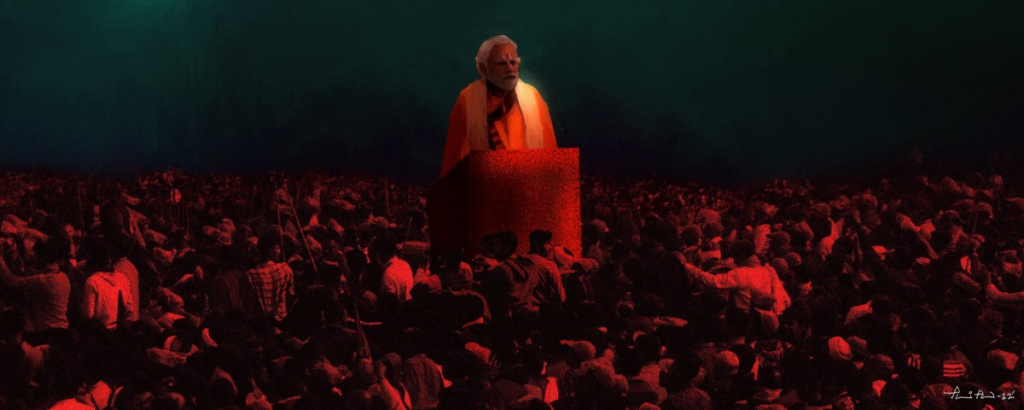

In the 12 years he was chief minister of Gujarat and the nine in which he has been the prime minister, Narendra Modi has shown, time and again, that he is built somewhat like a powerful automobile in which the manufacturers forgot to put in a reverse gear. Because throughout these years, his only response to every threat he has faced has been to launch a counter-attack, no matter what it might cost the nation or even his own future.

I had therefore been waiting for his counterattack to take shape ever since the opposition’s success in forming a combined front to fight the Bharatiya Janata Party in 2024, at Patna. I got my answer on July 5. Sharad Pawar had been the convenor who had made the Patna meet possible. So Pawar’s party had to be destroyed first.

The weapon that Modi has used is the one he has been using with increasing frequency against his political opponents and critics in civil society. This is the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, in which he made eight draconian amendments in 2019 that have given his government virtually unrestricted powers of arrest, detention and attachment of property, and all but abolished the habeas corpus, the right of the accused to remain free until convicted of a crime.

Since then, Modi has been relying more and more heavily upon the PMLA to ‘persuade’ his political opponents to betray their parties and join the BJP. His destruction of the Nationalist Congress Party has run true to form: four of the nine defectors – Ajit Pawar, Praful Patel, Chhagan Bhujbal and Hasan Mushrif – have been under investigation on a variety of money laundering and bank loan scam charges, and have had hundreds of crores worth of their properties sequestered. Now that they have become honourable ministers of the government and ruling party of the great state of Maharashtra, one can presume that these charges will disappear like the mists of the night at the rising of the sun.

That this has been Modi’s revenge on Pawar has been endorsed by no less eminent a journal than India Today, which has also warned that Bihar is next on the prime minister’s list. India Today has also surmised that this is only the beginning of a campaign that will be launched in other opposition-ruled states as well. Its purpose, the weekly has surmised, is to show to the people how unworthy of trust their representatives are and to remind them that only a party with a clearly stated ideology can be relied upon to fulfil its promises.

This is the challenge that the opposition now needs to meet. With the Lok Sabha elections less than nine months away, its first task must be to reassure the electorate that the unity achieved at Patna remains undented by the developments in Maharashtra. To do this, it needs first to highlight the progress it has made in removing the obstacles that have hindered the move from competition to cooperation. To say that this has been impressive would be an understatement, for the conclave reached an agreement not only on the yardsticks it would use to decide which party would contest which constituency, but agreed to leave the even more thorny issue of leadership to be decided after the elections. It also recognised the need to present an alternative vision of India’s future to the BJP’s Hindutva.

Despite these impressive achievements, doubts about the stability and longevity of the coalition have continued to persist. These have been fuelled to some degree by the absence of the chief ministers of Andhra Pradesh, Telangana and Odisha, and of Bahujan Samaj Party leader Mayawati, but their main cause is the explicit refusal of the Aam Admi Party to endorse the Common Declaration because it did not include a commitment to vote against the Delhi ordinance. Kejriwal need not have insisted upon this, because the ordinance is outrageous anyway, and would hamstring the Congress and BJP too, were they ever to come to power in Delhi. What is more, it was openly mischievous for Narendra Modi had lost this battle in the Supreme Court once already and was bound to do so again. Its sole purpose, therefore, was to give the simmering hatred of the AAP within the Delhi branch of the Congress an occasion to surface and thereby throw a spanner in the works of creating a unified opposition.

Mallikarjun Kharge and Rahul Gandhi’s failure to recognise this, and readily concede to AAP’s demand, was therefore a chink in opposition unity that virtually invited exploitation by the BJP. That is the chink that it is now trying to widen.

What is hard to understand is why this simple request has proved an obstacle to unity when much more serious obstacles have already been overcome. The only explanation is the impact that a concession by either party would have had upon its own party cadres. Despite the cementing and revitalising impact that Rahul Gandhi’s Bharat Jodo Yatra has had upon the Congress, its unity remains fragile.

In large parts of the country including, notably, Uttar Pradesh and Bengal, its repeated defeats at the hustings have made it virtually cease to exist. It cannot therefore be blamed for fearing that after suffering three successive Vidhan Sabha poll defeats, its cadres in Delhi are also headed out of the door. Ajay Maken’s relentless attacks upon AAP are therefore attempts to stem the rot, and the leaders of the Congress cannot be blamed for not reigning him in, because of the effect this could have upon the party’s cadres in other states where its dominance is endangered or has disappeared.

But Maken’s attacks upon the AAP have created a mirror image of the problem he faces within the Congress for Kejriwal within his own party. For through its silent endorsement of every attack that Modi has launched upon Kejriwal since 2015, Maken had made it virtually impossible for Kejriwal to join the opposition without some overt act of support for AAP in its constant battle with Modi.

What is important is for the opposition to convey to the public that in the battle to defeat Modi’s BJP in 2024, the differences between Congress and AAP signify nothing. AAP does not need the support of the coalition to rout BJP in either of the two states that it now governs. In Delhi it won 67 and 62 out of the 70 vidhan Sabha seats with a colossal 54% of the vote in 2015 and 53.6% in 2020. These are figures that the Congress did not even come close to matching either at the Centre or in any of the states from 1947 till 1989. In Punjab, AAP won 92 out of 117 seats last year with 42% of the vote. Against this, the Congress, BJP and Akali Dal together won only 23 seats with 23.9%, 6.6% and 18% of the vote, respectively.

The message these results send is unambiguous: whether the AAP joins or does not join the coalition formally in 2024 will make no difference to the number of seats it will win in the Lok Sabha.

Nor is there the faintest chance that AAP will enter into any post-poll alliance with the BJP, for not only has it suffered more at Modi’s hands than any other party, but it would destroy every tenet upon which its meteoric rise has been based. These are its complete disregard for caste, creed, colour and gender in its policies and governance, and its commitment to serving the poor instead of being served by the poor.

Finally, AAP will contribute more to the saving of Indian democracy by refusing to compromise on its demand for support in the Rajya Sabha and being willing to fight alone if necessary, than by making any of the compromises that will be necessary to become part of an alliance of political parties. For it will demonstrate to the entire nation that the era of entitlement politics, in which candidates demanded votes from the electorate on the basis of their caste or creed, has ended and that of service politics, in which votes have to be won by serving the people, has finally dawned.